【中國外交部長說,一些國家不跟臺灣進行官方往來,同中華人民共和國建交,是「順應時代潮流的正確選擇」。】會後,有記者追問王毅對「精日分子」(精神上把自己視為日本人)怎麼看,他說:中國人的敗類!http://bbc.in/2Ia3KdL

記者會結束後,有媒體記者繼續追問王毅關於「精日分子」的問題,問道:「外長,對精日分子不斷挑釁民族底線的問題您怎麼看?」,王毅駐足後,該記者近一步解釋道,有人穿日軍軍裝跑到南京大屠殺遺址前拍視頻,「侮辱南京大屠殺遇難者」,「精神上把自己視為日本人」。王毅隨即對記者表示:「是中國人的敗類!」

據中國媒體報道,3月3日一則拍攝於南京大屠殺遇難同胞紀念碑前的視頻顯示,一名男子在刻有"遇難者300000"的牆前錄製視頻,並多次提及侮辱性詞匯。該男子此前曾因在微信群內發佈「南京殺三十萬太少」等言論被網友舉報,2月23日被上海市公安局楊浦分局處以行政拘留5日處罰。

而2月19日,還有兩名男子身著仿製日本軍服在南京抗日遺址前拍照,被南京警方處以行政拘留15天處罰。

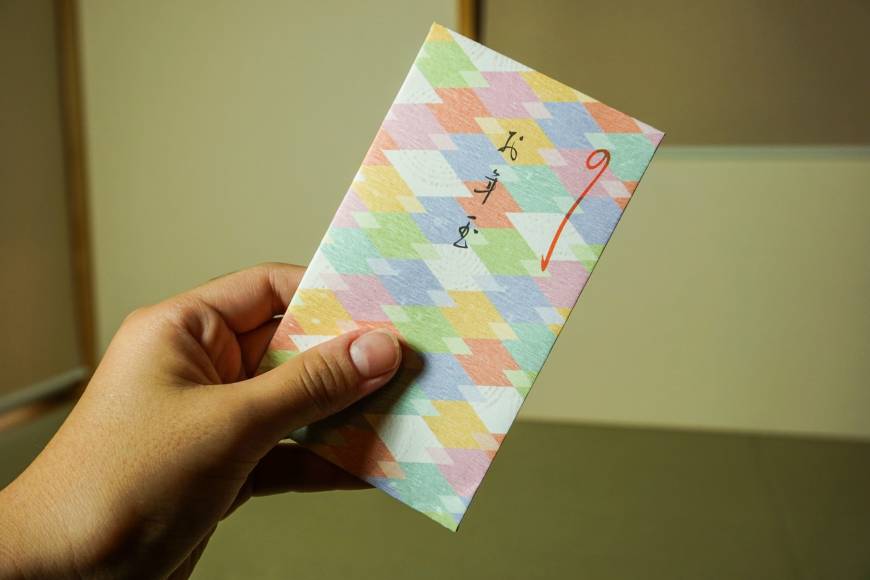

Money for kids: O-toshidama refers to the money children get from older family members to celebrate the new year. | GETTY IMAGES

Money for kids: O-toshidama refers to the money children get from older family members to celebrate the new year. | GETTY IMAGESLANGUAGE | BILINGUAL

Put your money where your mouth is

BY PETER BACKHAUS

CONTRIBUTING WRITER

JAN 8, 2018If it’s true that money makes the world go round, it does so mostly in silence. People like to have it, that’s for sure, but they’d rather have it without talking about it. Japan is certainly no exception in this department and yet, the Japanese money vocabulary is quite expansive, amazingly complex and certainly deserving of closer inspection.

Money, as such, is most commonly referred to as お金 (o-kane), where the honorific prefix “o” already betrays the taboo nature of the term. If you drop it and say something like 金が欲しい (kane ga hoshii, “I want money”), the money you announce to be in need of will come across as considerably “dirty” money or at least not particularly well-earned.

The same character is also commonly found at the end of money words, then read kin, to express various sorts of monetary transactions.

Most of the time, unfortunately, these are to a person’s detriment, as in the case of 借金 (shakkin, debt) or 罰金 (bakkin, fine). In addition, there are fees like入会金 (nyūkaikin, admission fee) and 入学金 (nyūgakukin, entrance fee for a school), as well as the nasty 敷金 (shikikin, deposit) and 礼金 (reikin, “key money”), both of which are often required when renting an apartment.

On the other hand, the good news is that there are also a few expressions in the 金 family that are about incoming rather than outgoing money. 年金 (nenkin, pension), for instance, provided there’s anything left at the end of the day. There are also various types of financial support, such as 助成金 (joseikin, grant-in-aid), 補助金 (hojokin, subsidy) and 奨学金 (shōgakukin, scholarship).

Another main entry in the Japanese money lexicon is 料 (ryō), as in 料金 (ryōkin, fee). Most annoying is the unspecified 手数料 (tesūryō, handling fee) that comes with even the smallest bureaucratic acts. When using toll roads, there will be 通行料 (tsūkōryō, toll), but that’s just peanuts in comparison with other fees that may be waiting down the road of life, such as, in order of appearance, 結婚仲介料 (kekkon chūkairyō,marriage brokerage fee) and 慰謝料 (isharyō, consolation money). 手切れ金 (tegirekin, alimony) is another word that may be used in times of relationship breakups, mostly adultery.

Less spectacular expenses are commonly expressed using the character 費 (hi, fee). These include 生活費 (seikatsuhi, living expenses), 交通費 (kōtsūhi, transportation costs), 教育費 (kyōikuhi, education expenses), 医療費 (iryōhi, medical expenses) and 維持費 (ijihi, maintenance costs), to name but a few. When it’s unnecessary (or just unwise, or both) to specify the nature of the expenses to be claimed, the catch-all 諸経費 (shokeihi, various expenses) can be used.

Like 金 and 料, 費, too, is frequently used for fees and charges. You’ll find it in terms such as 年会費 (nenkaihi, annual membership fees) and 参加費 (sankahi, participation fee). And if you are invited to a party that’s 会費制 (kaihisei, a system requiring membership or participation fees), be sure to bring some money because you’re expected to pay for yourself.

Incidentally, one of the very few words where 費 is not about losses but gains is the scientist’s beloved 科研費 (kakenhi), short for 科学研究費助成事業 (kagaku kenkyūhi josei jigyō), which is a research grant-in-aid funded by the Japanese government. The term for general research funding is 研究費 (kenkyūhi).

Also good to know is 賃 (chin), which occurs in the two terms 家賃 (yachin¸ rent) and 運賃 (unchin, fare for freight or passengers). In addition, it is frequently used in the context of income and wages, as in 賃上げ (chin-age, pay raise) or, the much less pleasant 賃金カット (chingin katto, pay cut).

Speaking of money for labor, another essential character in this lexical field is 給 (ryō), as in 給料 (kyūryō, salary, pay). Types of payments include 時給 (jikyū¸ payment by the hour), 月給 (gekkyū, monthly pay) and 日給 (nikkyū, daily pay). In addition, there are 日当 (nittō, daily pay) and 年収 (nenshū, annual income), both of which for some reason use different characters. Where more abstract language is required, people will go for terms such as 報酬 (hōshū, remuneration) or 手当 (teate, salary, allowance), as in 年末手当 (nenmatsu teate, year-end allowance), or what is more casually known as ボーナス (bōnasu, bonus).

When the idea of “exchange” is to be emphasized, 代 (dai, shiro) comes in handy. It occurs in expressions like 部屋代 (heyadai¸ room charge), 車代 (kurumadai, car charge), and 酒代 (sakadai or sakashiro, drinking money; tip).

Most conscious of the taboo to talk about money are terms like 月謝 (gessha, monthly tuition fee), which literally translates as “monthly gratitude,” as well as お礼 (o-rei, gratitude) and お祝い (o-iwai, celebration), which are expressions you’ll frequently read when envelopes with smaller and larger amounts change hands.

If you have spent the winter break in Japan, the term you must have come across most recently is お年玉 (o-toshidama). The word has no money characters, but it refers to the money children get from older family members to celebrate the New Year. It is said to have derived from an old ritual in which round rice cakes (餅玉, mochidama) were distributed in the household. Children will of course always appreciate it, by whatever name it comes.

沒有留言:

張貼留言